Reporters become bartenders and baristas while looking for work

By Gerry Smith Bloomberg

The news business is on pace for its worst job losses in a decade as about 3,000 people have been laid off or been offered buyouts in the first five months of this year.

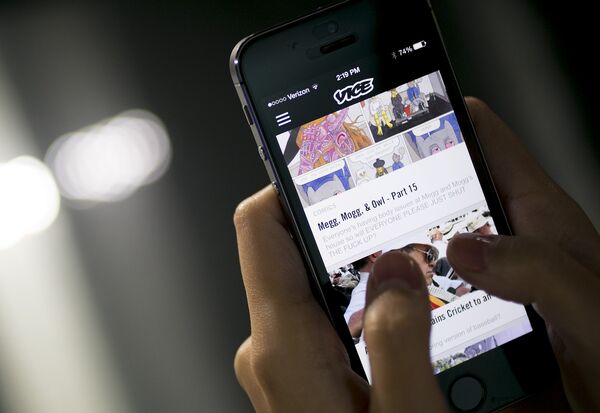

The cuts have been widespread. Newspapers owned by Gannett and McClatchy, digital media companies like BuzzFeed and Vice Media, and the cable news channel CNN have all shed employees.

The level of attrition is the highest since 2009, when the industry saw 7,914 job cuts in the first five months of that year in the wake of the financial crisis, according to data compiled by Challenger, Gray & Christmas Inc., an outplacement and executive coaching firm.

The firm’s tally is based on news reports of buyouts and layoffs, and includes downsizing at printing operations and advertising and tech executives at Verizon Media Group, home of HuffPost and Yahoo, which announced in January that it was laying off about 800 employees.

About 88,000 people worked in U.S. newsrooms in 2017, according to Pew Research Center.

With the U.S. unemployment rate the lowest since 1969, the journalism job market is one of the rare weak spots, said Andrew Challenger, the firm’s vice president.

“In most industries, employers can’t find enough people to fill the jobs they have open,” he said. “In news, it has been the opposite story. And it seems to have been accelerating.”

The cuts have created a competitive job market where the number of out-of-work journalists often exceeds the number of openings. When Bklyner, a local news site in Brooklyn, said in May it was looking for a new political reporter, 16 journalists emailed their resumes within a few hours, said Liena Zagare, Bklyner’s editor and publisher. Many had prior work experience at national media outlets such as CNN, Reuters and New York Magazine.

“I was looking at my inbox like, ‘Oh my goodness,’” Zagare said in an interview. “It was beyond what I’ve seen before — the kind of people looking to work for us and the speed that their applications were coming in. To me, it was incredibly depressing. It says something about this industry that we can’t employ these people.”

Bad News

U.S. newsroom jobs dropped 23% between 2008 and 2017

Source: Pew Research Center analysis of BLS data

There are a few reasons for the job losses. Local newspapers have seen much of their advertising revenue vanish as readers move online. They’ve also struggled to attract many digital subscribers after past rounds of layoffs and buyouts eroded their quality. Digital media startups, funded by venture capitalists seeking growth, aggressively hired journalists then scaled back to focus on profitability. Almost everyone is struggling to compete with Facebook and Google, which accounted for three-fourths of U.S. online ads sales last year.

The job instability in online media is one reason for the wave of unionizing across the landscape. At Vox Media, home of websites like the Verge and Eater, a new union contract ensures that employees get a minimum of 11 weeks of severance pay if they get laid off.

In January, John Stanton, a former Washington bureau chief for BuzzFeed News, was one of about 250 people cut from the company. In June, he helped start a nonprofit called the Save Journalism Project, which calls attention to how tech giants like Facebook and Google are threatening newsrooms by dominating the online advertising market.

So far, the group has published op-eds in newspapers, launched an advertising campaign and flown a plane over a Google conference with a banner that read “#savelocalnews.”

“We’re trying to get our colleagues to speak up,” Stanton said. “We need to protect ourselves or we’re not going to have jobs.”

Many BuzzFeed journalists who were laid off in January are still looking for full-time work, he said. Several are freelancing, in some cases writing 1,000-word articles that pay about $400 and take a week to complete. “The pay freelancers get is completely inadequate,” Stanton said.

While tech giants are often blamed for the news industry’s financial troubles, they have also become a destination for journalists who want to leave the field. Amazon is hiring editors to cover local crime news for a division of its security-focused doorbell, Ring. Facebook, Apple, Snapchat and Google have all hired journalists in recent years to work on their media-related initiatives.

The journalism job hunt can be particularly challenging between the coasts. Last year, Emma Roller, 30, took a buyout after working as a politics writer for the website Splinter, which was part of Univision’s Gizmodo Media Group. She got married and moved from Washington to Chicago to be closer to family. But as she looked for a new job, she found many positions required that she live in New York, Washington or Los Angeles.

“All of media has become concentrated in three cities,” said Roller, who now works part-time at an elementary school and as a barista at a coffee shop while freelancing. “I chose to move away from where journalism jobs are. But at the same time it’s a structural problem.”

Journalism schools say enrollment is up, despite the dark headlines about the industry, and they are adjusting their curriculum to prepare students for in-demand jobs. The University of Maryland expects 44 graduate journalism students this fall, up from 32 last year. The school has started requiring students take more audio reporting classes because “this generation seems to love podcasts,” said Lucy Dalglish, dean of the Philip Merrill College of Journalism.

Some news outlets are growing. The Los Angeles Times has added about 100 employees to its editorial staff since billionaire Patrick Soon-Shiong bought the newspaper last June. The Washington Post announced recently it is adding 10 people to its investigative team.

But for some journalists, even winning national awards is not enough to help make ends meet. More than two years ago, Chris Outcalt took a chance on a job at a startup that wanted to launch a technology news website. But the team was laid off before it got off the ground. So Outcalt began freelancing.

In June, Outcalt won a Livingston Award, a prestigious prize given to journalists under the age of 35. Yet he’s still searching for a full-time job. In the meantime, he’s started working part-time as a bartender at a craft brewery in Denver to help pay the bills.

“I’m often thinking about whether I’ll be able to hang on until I find something a little more stable — something, say, that provides health insurance,” Outcalt said. “Certainly no one becomes a journalist to get rich. But I also can’t imagine there are that many people who would want to enter a challenging profession that also requires you to tend bar two nights a week.”