Addis Ababa(ANN)-After launching the most ambitious reforms in his country’s history Ethiopia’s Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed, is under threat. The murder of his army chief of staff amid an alleged coup attempt in the Amhara region has highlighted the vulnerability of the reform process. The BBC’s Africa Editor, Fergal Keane, analyses the challenge facing the continent’s youngest leader.

Just a few weeks ago, Abiy Ahmed was riding high and feted across Africa as a reformer.

He had released political prisoners, appointed women to more than half of his cabinet posts, persuaded a noted dissident to head the country’s election board, and staged an historic rapprochement with neighbouring Eritrea after decades of conflict.

When I met him in December last year he was brimming with confidence, even telling me that the world should look to Ethiopia “to see how people can live together in peace.”

Millions at risk

Now after an alleged coup attempt against the Amhara regional government which killed his army chief of staff and close ally, General Seare Mekonnen, Mr Abiy’s position and the future of his reforms look much less secure.

The alleged instigator of the coup was shot dead and a wave of arrests followed. But nobody with any knowledge of Ethiopia believes this is the end of the matter.

With nearly 2.5 million people displaced by ethnic violence and deep divisions within the ruling EPRDF coalition, Mr Abiy is acutely vulnerable.

He is to some extent a victim of his own reformist zeal.

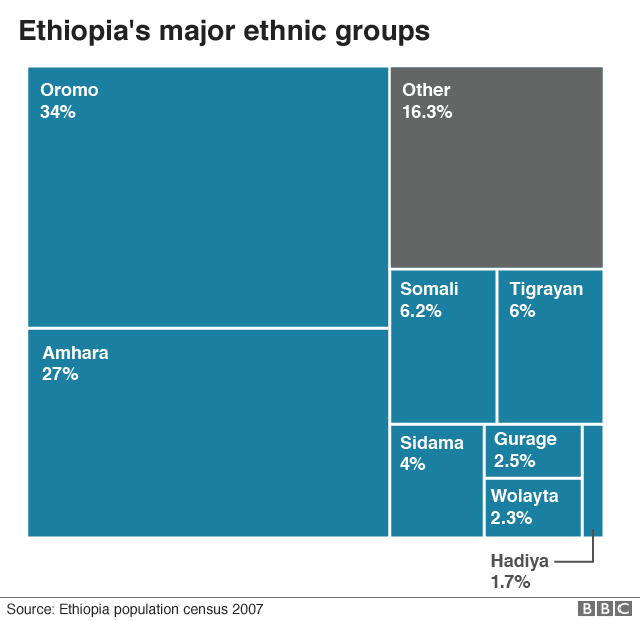

Ethiopia is made up of nine different self-governing ethnic regions.

Ethnic nationalism was kept ruthlessly in check under the Marxist Dergue regime and during the two decades of EPRDF rule that followed. The opening of the political space under Mr Abiy has lifted a lid on ethnic tensions

Ethiopia’s system of ethnic federalism was always going to be vulnerable to politicians playing on atavistic sentiments.

And the speed of Mr Abiy’s reforms has unsettled the four party coalition that makes up the ruling party. There is acute alienation among Tigrayans who comprise just 6% of the population but dominated the previous government.

‘We want you to leave’

In Oromia and Amhara – the two most populous states – smaller parties have emerged appealing to crude ethnic sentiment. The man suspected to have masterminded the Amhara coup attempt was also accused of recruiting an ethnic militia.

In the Somali ethnic region I visited a refugee camp that was host to some of the 700,000 people who had fled ethnic clashes with their Oromo neighbours. Think of the scale of those numbers and the individual suffering involved.

I recall the words of an elderly woman who had travelled for weeks to reach the camp.

“We were living in peace but the Oromos living in that area said: ‘Your numbers along with other Ethiopians is growing and we want you to leave’. Then conflict started afterwards and they slaughtered our men and killed our children, and that is why we came here looking for peace.”

Having reported on ethnic conflict in Europe, Asia and Africa I found her words chillingly familiar.

The experience of Ethiopia under Mr Abiy underlines the old truism that the most vulnerable moment for any authoritarian state is when it starts to reform. Under dictatorship ethnic hatred does not vanish. It simply gets driven underground.

The examples throughout history are numerous. Consider the case of the former Yugoslavia which descended into a series of savage civil wars after the end of Joseph Broz Tito’s long reign.

But Yugoslavia did not descend into civil war simply because of so-called “ancient hatreds”. It took unscrupulous leaders – notably Slobodan Milosevic of Serbia and Franjo Tudjman of Croatia – to create the horrors of ethnic cleansing in late 20th Century Europe.

You may also be interested in:

Mr Abiy is not of the same ilk. His broad vision is progressive and inclusive.

But I recall a conversation with one of his critics in Tigray, Getachew Reda: “Abiy is a very driven, very ambitious man. He symbolizes the kind of ambition, the kind of courage to storm the heavens that youth would represent, but he also represents the kind of tendency to gloss over things, the kind of tendency to try to telescope decades into months, years… to rush things.”

Ethiopia’s prime minister now needs to move carefully. The wave of arrests that followed the attempted coup – more than 250 people are in custody – runs the risk of deepening resentment in Amhara.

The blockage of the internet in recent weeks may have been intended to frustrate the mobilising capacity of his enemies, it felt very far from the open government Mr Abiy promised. The country is awash with rumour and speculation.

- Born to a Muslim father and a Christian mother on 15 August 1976

- Speaks fluent Afan Oromo, Amharic, Tigrinya and English

- Joined the armed struggle against the Marxist Derg regime in 1990

- Served as a UN peacekeeper in Rwanda in 1995

- Entered politics in 2010

- Briefly served as minister of science and technology in 2016

- Became prime minister in April 2018

Elections are due next year but already senior officials are doubting whether they can go ahead. Last year’s local elections were postponed because of unrest.

I met the head of the election board, Birtukan Mideksa in Addis Ababa last December when there was still optimism about polls. She is a former dissident invited home from exile by Mr Abiy.

“To have, like, a former opposition leader, former dissident, to lead an institution with, you know, significant independence of action, you know, it means a lot,” she told me.

“So, of course, it needs a lot of collaboration, to institutionalize democracy, and have meaningful election and free media on, you know, independent institutions. But I’m very hopeful we will do differently this time around.”

Now she is warning that elections may have to be delayed, telling Reuters news agency that if “the security of the country is not going to improve, we can’t tell voters to go and vote”.

Yet cancelling elections is likely to increase polarization. The balance between security and freedom could not be harder to achieve.

Mr Abiy’s great challenge is to build a coalition for change across the ethnic groups. That will take persuasion.

It will demand restraint. And it will require balancing of groups and interests in government. Besides his abundant youthful energy Abiy Ahmed is going to need more of the wisdom of age.

Source: BBC