By Jessica Roy – Elle

We’re here to determine whether the woman is a terrorist, but all Lori sees is her sister. The gait and the posture she would recognize anywhere, even through her khaki prison uniform. The tattoo, a pair of puckered lips on her neck, peeking over the collar. She has Lori’s natural brown hair color, now gray at the roots. Sam is Lori’s older sister, but Sam was the one always getting in trouble. Parties, older boyfriends, dead-end jobs, dead-end marriages. And now, three federal charges: providing material support to ISIS, aiding and abetting ISIS, and lying to the FBI.

The Justice Department says she supported ISIS, anyway. This is a procedural hearing today, part of the big case against her. U.S. law enforcement has known about Sam since at least November 2017, when she was interviewed by FBI agents in a Kurdish-run prison camp in Syria. Before that, she had been living for more than two years in Islamic State–controlled territory in Raqqa with her four young children.

.

In the days and weeks leading up to this hearing, Sam has told the FBI,

told her lawyers, told anyone who will listen that she was the victim

of an abusive husband. He was Moroccan, but they met in Indiana. He used

to be so much fun, she told them. They went skinny-dipping. Then,

little by little, he started to slip into darkness. It was slow at

first, almost too slow to realize what was happening, but then so fast,

like a blur—there she was in Turkey, on the Syrian border, and her

husband was threatening to kidnap her daughter if she didn’t go with

him.

How does a woman from Arkansas, a woman who used to wear makeup and take selfies and wear flip-flops, end up dragged across the border into a war zone by her fun-loving husband? How do you grow up in the United States of America, surrounded by Walmarts and happy hours and swimming holes, and end up living in Syria under a terrorist group?

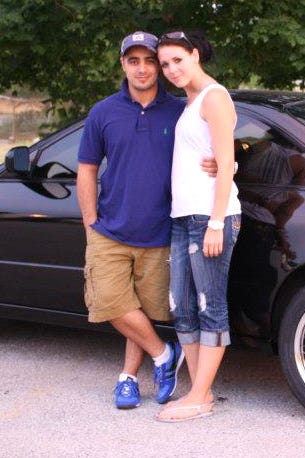

Samantha Sally met her husband Moussa Elhassani in Elkhart, Indiana. A few years after meeting, she says he forced her to move to Syria so he could fight for ISIS. Samantha Elhassani

Lori, maybe more than anyone, knows how. She’s the reason Sam moved to Indiana. And the bad guy Sam married, the one who became an ISIS fighter? He was Lori’s brother-in-law. The two sisters married two brothers. Lori was there with Sam, until Sam was gone, beyond reach. Until not even Lori knew whether what the Justice Department claimed—that Sam was an accomplice, not a prisoner—was untrue.

Lori passes through the metal detectors and makes her way to the fourth-floor courtroom, which is circular and paneled with brown oak. Sam seems to sense her little sister come in, and she looks up and smiles, gives a small wave. Lori slides into a bench near the back.

How does a woman from Arkansas end up dragged across the border into a war zone by her fun-loving husband?

The hearing lasts less than a half hour, most of which is taken up by the judge posing procedural questions. At the end, after the lawyers finish their statements, the woman again gives a nod to her younger sister, who responds with an encouraging smile. An armed guard leads the woman out of the courtroom, back down the hall and down the elevator, out to the waiting prisoner transport vehicle, back to the Porter County Jail.

Samantha Sally is 34 years old, and her sister loves her. Sam has made some mistakes. Lori made mistakes too. Sam’s happened to be colossal mistakes, and with the wrong guy. Could it have happened to Lori? Could it have happened to anyone?

When the FBI arrested Sam, she was living in a tent—Sam and her four kids. Miriam was one year old, and Ishmael was two. Sarah, her older daughter, was five. These are her children with Moussa Elhassani, who was a fun-loving guy in Indiana when she met him. And Matthew, 10, is her son from a previous relationship, back in Florida, where she lived for a time.

Samantha Sally sits in her tent in the Roj refugee camp in Al Hasakah, Syria, cooking food over a propane burner. Samantha Elhassani

The plastic tent was about the size of a large closet. There was hardly any ventilation, which made it either hot and sticky or bitter cold, depending on the weather. There was barely enough room for them to lay down on the floor together to sleep.

The Roj detention camp in Syria houses refugees fleeing the region’s surrounding conflicts, many of them some of the hundreds of women from around the world who married men who joined ISIS. When the makeshift ISIS government—its self-declared caliphate—crumbled, these women escaped, and now they live in plastic tents with their children, awaiting to be accepted back into society. From November 2017 until July 2018, Sam Sally was one of them.

Sam used a

small plastic water cooler for a chair, and the family slept together in

a pile, huddling close against the cold. She cooked what food was

available—usually dried peas and rice, rarely anything fresh—over a

propane burner. They had to squat over a hole in the earth to relieve

themselves, and diapers were scarce. Tuberculosis and hepatitis ravaged

the camp. Sam and Ishmael both contracted Hepatitis, and were put on

antiviral medications; her youngest children, Miriam and Ishmael, were

malnourished and weak. Sam believed she was losing them.

Samantha and her children Ishmael and Matthew in their tent in the Roj refugee camp in Al Hasakah, Syria. Samantha Elhassani

She didn’t have internet and cell phones were rare,

but Sam was cunning. She developed a relationship with one of the

guards at the camp—his name was Ahmed—and convinced him to let her use

his phone to send messages to Lori, back in Indiana.

Sometimes, she told Lori, the situation wasn’t all that bad—she admired the Kurdish all-female military units fighting ISIS and said Matthew wanted to join the Kurdish men’s militia. And hey, Sam said: It was better than being in jail.

But other times, Sam left messages that were frantic with terror.

In December of 2017, more than two years since Sam first left Indiana—where they had lived together, where Lori had watched Sam give birth to two children, Lori’s niece and nephew—Sam sounded lost. She seemed trapped between her two lives, committed to neither. Voicemail From Samby ELLE US.

“Sorry I’ve lost my voice but I just want you to know that things are getting really tough here and I don’t have any way to provide for my kiddos and things are hard. And I need your support now more than I need it ever right now. I know you hired a lawyer to try to get our passports in line and as quickly as we can get this done… things are getting pretty hard. I can’t tell you anything but we just need to get out of here, we need to get out of here, we need to get out of here quick.”

The next time Lori saw Sam, it was on CNN. A London-based field producer named Salma Abdelaziz had been in Mosul reporting on a British terror cell when she heard that a young boy named Ayham had surfaced near Mosul speaking perfect English. He was Yazidi—a minority ethnoreligious group concentrated in northern Iraq and Syria—and he claimed to have lived with an American woman he called “Um Yusuf” (mother of Yusuf) and her children in Raqqa.

For months Abdelaziz asked around about the American woman. Kurdish authorities eventually pointed her to Roj. Eager for other nations to remove their citizens from the camp, the Kurds agreed to bring Sam Sally and her kids to a safehouse outside the camp, so that Abdelaziz, CNN correspondent Nick Paton Walsh and their crew might motivate the United States to repatriate them.

Samantha Elhassani and her children Sarah, Ishmael, Matthew and Miriam during an interview with CNN in Syria. CNN

When Sam walked into the lime green-painted living room of the safehouse, Abdelaziz and the CNN team were surprised. She looked nothing like the other wives of foreign ISIS fighters they had encountered. She was wearing western clothing—a brown button-down, black sweatpants and a black puffy vest—and her aqua eyes were ringed with heavy eyeliner. She had multiple piercings in each ear, and one in her nose. And that pair of puckering blue lips tattooed on her neck.

She looked nothing like the other wives of foreign ISIS fighters they had encountered

Sam settled into the room’s low-slung purple couches, folding her legs primly beneath her. She laughed and joked with her guards, whom the kids climbed like a jungle gym.

The only child who seemed attuned to the strangeness of the situation was Matthew. In Syria, he had developed a seriousness that made him seem older than he was. To Abdelaziz it looked as if Sam relied on Matthew in a way mothers don’t usually rely on their 10-year-old sons. Throughout the interview, Matthew, clad in a maroon turtleneck and jeans, ably bounced baby Miriam on his knee to keep her from crying.

The

team of CNN journalists had brought energy bars and candy, which the

kids ate while Sam began the interview. She seemed abnormally calm and

happy, Abdelaziz thought, for someone raising four kids alone in a tent

in a country at war. Abdelaziz had only just met Sam, but she sensed

some misplaced hubris that made Sam confident that she would be

exonerated for what she’d done. Did she really think her husband was

taking her on a “vacation” to the Syrian border, they asked. What about

those trips to Hong Kong she made, opening bank accounts and purchasing

weapons?

Sam grew defensive. “I was like a prisoner,” she told them. “I had no choice.”

Sam was good with the kids, according to Abdelaziz, and seemed happy to be out of her marriage. “But she didn’t seem aware of how obvious the holes in her story were and how much they would draw questions to her narrative,” Abdelaziz said. “I don’t think she realized, because she was very defensive when we would push on those obvious gaps in her story.” She didn’t realize how much she could seem like a willing participant in the horrors of terrorism.

At one point, Sam volunteered, unprompted, that she had purchased Yazidi child slaves in order to “protect” them. ISIS had codified the enslavement and rape of Yazidis, and Sam didn’t seem to understand the gravity of her involvement, that she could be accused of willingly participating in human trafficking and attempted genocide. “I would never apologize for bringing those girls to my house,” she said. “They had me and I had them. And we knew that if we were just patient we would stick together. You understand? We cooked together, we cleaned together. Drank coffee together. Slept in the same room together. I was like their mother.”

Ayham Azad, a Yazidi Iraqi boy, was taken as a slave by Samantha Elhassani and her husband Moussa. Ayham says Samantha treated him like one of her own children. Tahsin Shahwan

Ayham, the 9-year-old who tipped CNN off to Sam’s presence in Syria, was the family’s third slave. His uncle, Tahsin Shahwan, believed that Sam did treat them like her own children and says that Ayham adored her. “She is a really nice person, and her way of seeing is different than ISIS,” Shahwan told ELLE. But Sam’s husband Moussa raped the family’s female slaves.

“Do you now not regret enabling their serial rape?” asked CNN’s Paton Walsh.

“No one will ever be able to imagine what it is like to watch their husband rape a 14-year-old girl. Ever,” Sam told them. “And then she comes to you—me—after crying and I hold her and tell her it’s going to be okay. Everything is going to be fine, just be patient.”

When Lori saw the interview, she thought, this is the bottom.

This is the hideous, twisted universe where other women live, not Samantha Sally from Arkansas. A place that exists only on the news, a place that is part of no woman’s life plan, a place in which it’s impossible to end up, because so many things would have to go wrong, a perfect, horrible, unlucky cascade of bad things, and that…just doesn’t happen.

This is the hideous, twisted universe where other women live, not Samantha Sally from Arkansas.

Except that it happened to Sam.

And it happened to the woman in the next tent.

And the woman in the tent after that.

Sam’s children Sarah and Matthew pose with a kitten in front of a home destroyed by an airstrike in Raqqa, Syria. The explosion killed their aunt. Samantha Elhassani

You have to understand: Sam was living in a country within a country, a war zone controlled by terrorists. It seemed lawless, except that these men were creating their own new laws, enforcing them with torture and murder. Lawlessness would have been easier.

After she crossed the border from Turkey to Syria with Moussa and her children, Sam was put into a dormitory with other women while her husband completed mandatory ISIS military and religious training. She didn’t see Moussa for weeks. And then, one day, there he was: Sauntering down the street, a huge smile on his face and a gun slung over his shoulder. Moussa, who used to be a little scruffy back when she loved his round face, the smile that made his eyes into sleepy half-moons, had grown the same bushy beard as his new comrades.

Sam ran up to him and screamed. “You’re crazy and I’m leaving,” she said.

Moussa just grinned. “Go ahead,” he said. “You can try, but you won’t make it.”

The family lived in a small home on the outskirts of Raqqa. The walls were sun-bleached and pockmarked with bullet holes, and stray cats roamed the rubble that ringed it. Bombs fell several times a day; shrapnel, rocks, and glass rained down. The bombs were louder than anything Sam had ever heard, each one a lightning bolt to the brain.

Sam refused to convert to Islam or obey ISIS’s rules about how women should dress. Surely, to her husband’s associates, she behaved more like the western enemy they were fighting than a pious citizen of the caliphate they were struggling to build.

When an escape plot Sam says she tried to engineer was discovered, ISIS security forces arrested Sam, who was then pregnant, along with Moussa. They brought them to what had become known as the Black Stadium, a former soccer stadium in central Raqqa where executions and beheadings were put on public display. The stadium’s maze of subterranean locker rooms had been converted into jail cells and torture chambers, and Sam was taken to one and strung up by her wrists, beaten and raped.

Sarah, Ayham and Matthew on a motorcycle with their uncle Abdelhedi Elhassani, an ISIS fighter, in Syria. Sam and her children lived for a time with Abdelhedi after her husband Moussa was killed in an airstrike. Samantha Elhassani

“I was tortured, I was beaten—just the sickest things that you could possibly imagine happened to me,” Sam told Mother Jones in 2018. “I was told that they were going to do everything to me that the Americans did to their brothers in Guantánamo Bay. You hear screams, you see blood on the floor. It’s all night: sleep deprivation, hunger, living in your own filth, regular beatings, the humiliation, electrocution. You stay in a cell that you can’t even stretch your legs in. There’s no toilet, there’s nothing. You just can’t imagine. They hang you up by the ceiling and they strip you naked and they beat you in front of a bunch of men. They take their imagination and they just roll with it.”

Bombs from the Syrian army destroyed parts of the jail around her. Eventually Sam and Moussa were brought before ISIS judges, who decided to release them. At nine months pregnant, psychologically and physically injured from the torture, she resettled back into the house near Raqqa. Moussa went off to the front lines to fight. Sam gave birth to a son, Ishmael, and in 2017 she had Miriam. The bombs and the roving ISIS police meant Sam spent most of her time indoors. Loneliness grew on the house like mold.

Samantha, malnourished and underweight, sits in her tent in the Roj refugee camp after fleeing ISIS-controlled territory. Samantha Elhassani

One night when Moussa was home on a brief furlough, he suggested they buy a Yazidi slave to keep her company. They went to the house of one of Moussa’s friends and Sam met Soad, a 15-year-old girl. Sam used half of the savings she’d brought with her to Raqqa— $10,000—to buy her.

“When I met Soad I would not leave without her,” Sam said. “I fell in love with her when I first met her. She was just so heartbroken and so broken in general because of what happened to her.” ISIS captured Yazidi girls to make them sex slaves, but Sam said Moussa wasn’t interested in Soad at first. “It wasn’t until later that he was interested in her because she had become healthy and she was happy.”

Soon Moussa decided to purchase Bedrine, a younger girl, and Ayham. The two girls and Sam cooked and cleaned together and at night they slept in the same bedroom. Ayham and Matthew became friends.

“Bedrine, Ayham and Soad are probably the strongest people I’ve ever met in my life,” Sam told me. “Even when things bother them they try to push through, and they gave me strength to not show my fear and to not show my children fear. They gave me hope that we would survive, and that we would all be going home.” She talks as if they were all in it together, them against Moussa. “They were complacent, but not at the same time, which was really awesome because it made my husband’s life hell. We all kind of did our part to wear him down.”

A year into their time in Syria, ISIS soldiers came to Sam’s home and insisted Ayham and Matthew—whose name Moussa had changed to Yusuf—appear in a propaganda video.

Sam says she refused, and fought so hard to keep the boys from being filmed that the soldiers broke several of her ribs. “They put the gun in her head [and] they said you have to do it. And then she said okay and then they did it,” said Ayham in an interview with CNN. “Watching it, it turned my son into something that he wasn’t,” Sam told me. “It is pure propaganda. It makes him seem like a threat. It really broke my heart. It was hard. And it was very very hard to swallow.”

The slickly produced, seven-minute video presents Raqqa not as the shell of a city it had become, but as an Islamic utopia teeming with fierce warriors hellbent on destroying the West. Matthew appears less than a minute in, his head covered in a black scarf, hunched over a rifle while a sniper teaches him how to shoot. “My name is Yusuf and I’m 10 years old,” he says in Arabic-accented English, staring straight into the camera. It’s obvious he’s reading off a script, and his pained expression makes it clear he doesn’t want to be there. “My message is to Trump, the puppet of the Jews,” Matthew says in one of the final scenes, simultaneously absurd and chilling. “Allah has promised us victory and he’s promised you defeat. This battle is not going to end in Raqqa or Mosul. It’s going to end in your lands. By the will of Allah we will have victory. So get ready, for the fighting has just begun.”

But the battle in Raqqa was coming to a close. By February of 2017, U.S.-backed Syrian forces were closing in, and Moussa was wounded in an airstrike when a piece of shrapnel struck near his spine. According to Sam and Tahsin Shahwan, the uncle of Ayham, the family fled Raqqa in ISIS vehicles and landed in Deir ez-Zur, a city in eastern Syria. While Moussa was convalescing, Sam lived for a time with his brother Abdelhedi, until a final bombardment killed Moussa and crushed the remaining soldiers of the Caliphate. An email sent by Abdelhedi says Moussa died on September 6, 2017 after a rocket struck the building he was in. Six weeks later, Sam paid a trusted neighbor to drive her and her kids into Kurdish territory, where they would finally be out of ISIS’s control.

“It was terrifying. It was absolutely terrifying,” she told me. ISIS soldiers had tried to discourage defectors with horror stories about the Kurds. “We were told that Matthew would be executed, possibly Ayham, because they were both of fighting age. We were told that we would be put in prison, that we would be tortured and raped, and everything that the Islamic State did in their prison. ”

All that way, from Raqqa to Deir ez-Zur to the Kurdish red line, Sam had kept a 9 millimeter glock loaded and chambered under her hijab in case anything went wrong. As the smuggler pulled up next to the Kurdish military vehicle that was waiting for them, Sam knew it was the moment of truth. She waited until the very last minute, and then, when she couldn’t possibly wait anymore, she pulled the gun from beneath her headscarf, unloaded it and handed it to the smuggler. Then Sam Sally and her seven charges slowly emerged from the car, and took their first steps towards home.

Samantha and Moussa shortly after meeting in Elkhart, Indiana. Moussa’s brother Saleheddine says before moving to Syria, Moussa “was a regular man, a regular Muslim, doing his prayers and working hard.” Samantha Elhassani

In Elkhart, Indiana you work a crappy job, and you live in a clapboard house with a sagging roof, and you wait to die.

That’s how it felt to the Sally sisters, anyway. The yards were full of fast-food trash, cigarette packs, and the carcasses of old cars left to rot in the snow. In the local McDonald’s one morning, a toddler watched cartoons on the TV while her father nodded in and out of consciousness.

Lori was living in Elkhart and working at her husband’s shipping company, ViaAddress. They owned a home with two separate apartments. Sam had recently been laid off from her job in Oklahoma, and Lori was on the verge of divorcing Yassin, so she invited Sam to move in with her so they could support each other. “When I got there, nothing was like what she said,” Sam told me. “She was not divorcing her husband, the house was wrecked, it was a disaster. The job was crap. It was making minimum wage. It was just … I was really trying to make the best of it.”

Sam began hanging out with Moussa, the brother of Lori’s husband, Yassin. Moussa had come to the U.S. from Rabat, Morocco, in the early 2000s. He studied engineering at Fresno State University, but never graduated and later moved to Indiana to help Yassin with ViaAddress.

Samantha and Moussa Elhassani on a helicopter ride in happier times. Samantha Elhassani

One warm summer night a few days after Sam moved to Elkhart, Moussa took her to a small man-made waterfall in High Dive park. The street lamps were on and it was close enough to the bike path for people to see them, but they were high on the buzz of a new crush and decided to go skinny dipping.

Lori says Sam returned to her house late that night giddy, raving about how great Moussa was. Lori warned her sister that he was trouble—maybe even dangerous—but Sam couldn’t hear that. A few weeks later, she moved in with him.

One choice leads to another choice, and if you make enough bad ones in a row, bad choices become the only kind you seem to make.

In July 2012, a year after Moussa and Sam met, the two got married in a casual ceremony at home in Indiana. At first, Moussa lavished his wife with gifts and praise: “I know my husband loves me sooo much :)” Sam wrote on a photo posted to Facebook in November 2013 of a Subaru SUV. “on our way back from Pennsylvania with a new to me SUV!!” Moussa’s older brother Salaheddine, who lived with him in the U.S. for a time but now resides in Casablanca, said “he was a regular man, a regular Muslim, doing his prayers and working hard.”

Moussa could be wonderful with Matthew, who was 4 years old when Sam married him, and Sarah, the daughter they had together in June 2013. This one morning, Moussa was crawling around the living room floor, pretending to be a monster—he turned his eyelids inside-out, which the kids called his “eye trick.” Matthew and Sarah, wearing their footie pajamas, pretended to beat the monster away, and Moussa kept crawling back at them, until eventually he made his eyes normal again, spread his arms wide, and smiled that smile that took up his whole face. “Hi!” he sang out, and the two toddlers tackled him with hugs.

But over time, other sides of Moussa emerged. Several of Sam’s friends and relatives said that Moussa was physically and emotionally abusive. (Moussa’s ex-wife Amber Elhassani told ELLE.com she left him after he hit her during an argument about finances, but she was shocked to hear he had joined ISIS. “My mind’s trying to mesh the two people, the person that I knew and the person that I’m seeing in these videos,” she said. “It just makes you kind of rethink your entire—what you knew about that person.”) In 2012, after Sam and Moussa were married, he held Sam down on the floor and started to tear off her clothes. “Go get the scissors,” he said to Matthew, “So I can finish the job.” Sam says Moussa made her dye her hair blonde, lose weight, and get plastic surgery.

“She told me she didn’t like living there,” Angela Benke, who worked closely with Sam at ViaAddress, said. “She wanted out. And he hit her. I said, ‘Why are you staying?’ But she loved him. So, yeah. That’s kind of how that went. She was afraid of him, so she would rather have him right there than looking over her shoulder, I think.” Moussa Elhassaniby ELLE US

He mocked her. One winter day before Sarah was born, while he drove and Sam rode in the front seat, Moussa chided her in a high-pitched voice, imitating her demands: “I want a drink. And I want this and I want that. And I’m pregnant,” Moussa whined, pointing to his belly. Humiliating her.

In November 2014, court records show that Moussa proposed a strange plan: He wanted to move to Syria with his brother Abdelhedi, and he wanted Sam and the kids to join him. (Sam denies having advanced knowledge of Moussa’s plan to move to Syria.)

ISIS was at the height of its power in Syria, having recently captured Raqqa and declared it the capital of the caliphate. The group’s notoriety began creeping into the consciousness of Americans: they released brutal execution videos, including one of the beheading of the American journalist James Foley. President Obama authorized the first airstrikes targeting ISIS.

Sam wasn’t Muslim, and Moussa himself had never been particularly religious. He certainly didn’t abstain from alcohol or drugs or premarital sex. But maybe this wasn’t based in religion. Maybe it was business: Westerners like Moussa hoping to join the violent extremist group were promised gold, power and, of course, a place in heaven. They could live in the lavish homes rich Syrians had abandoned and amass wealth and influence, a promise that was surely compelling to a couple living a modest life in a midwestern town.

Then things got stranger: Moussa pressured Sam to make trips to Rabat and Hong Kong. On January 11, 2015, documents filed in Federal Court in Indiana show that Sam, Matthew and Sarah traveled to Istanbul and then onto Rabat, where they stayed with Moussa’s family for 10 days. “Defendant has given several inconsistent explanations of this trip,” the government document reads. “In one instance, she claimed that her family was considering a move to Morocco, and that the purpose of this trip was to check out cheap properties that were supposedly for sale. The government learned during its investigation that Defendant never went house hunting while she was in Morocco.” Furthermore, the U.S. Attorney stated in that document that one of Moussa’s family members confronted Sam about Moussa’s interest in ISIS while on the trip. “Defendant responded that she supported Moussa and would follow him anywhere,” the document reads. “Defendant indicated that they may start in Morocco before heading to Syria. When it appeared obvious that the family member did not share her views and could not be persuaded otherwise, Defendant dropped the subject.”

Before he moved the family to Syria, Moussa began taking Samantha’s son to a local shooting range in Indiana. Samantha Elhassani

Moussa’s brother Salaheddine, who remembers briefly meeting Sam during one of her visits to Casabalanca, says the Elhassani family had no idea of Moussa’s budding interest in ISIS. When their father told him Moussa had moved to Syria, Salaheddine was shocked. “I never knew that they would do the kind of thing.”

On February 17, 2015, a few weeks after returning from Rabat, Sam and Matthew went to Hong Kong and opened a safe deposit box. A month later, they again made the trip from Chicago to Hong Kong, staying for only one day. Just four days after returning, on March 22, 2015, Sam, Matthew, Sarah and Moussa boarded a plane to Hong Kong for the last time, where they met Moussa’s brother Abdelhedi and, according to the U.S. attorney, purchased tactical gear like binoculars and rifle scopes. On April 7, they flew to Istanbul, where court documents show they were supposed to continue on to Casablanca. The family never boarded that flight. Instead, Moussa took them to Sanliurfa, a city near the Syrian border known as a crossing point for smugglers making their way between the two nations. Sam claimed he told her it was a “vacation.” For four days he forced her to stay in the hotel while he disappeared, claiming it was too dangerous for her to go out.

“Moussa was the ultimate villain,” Sam told me. “He was seductive and his words were amazing. He just knew what to say and he knew how to move and he knew how to act where I didn’t know I was falling into a pit. It was like quicksand. It was so slow and the more I struggled the further I slipped…I just never saw it happening until it was absolutely too late.”

Women follow their husbands’ commands for all kinds of reasons, even when they know they shouldn’t. Sometimes, the danger accumulates so slowly as to be imperceptible. For Sam, it was now the opposite: Everything happened too fast. Moussa was creating chaos, and amid that chaos she lost her power to think.

The accumulation of bad choices had led her to this moment when she had no choice at all.

By the time he did the thing that jolted her into

reality—by the time he grabbed their 2-year-old daughter and held her

hostage, threatening to take her to Syria with or without Sam—it was too

late.

The accumulation of bad choices had led her to this moment when she had no choice at all.

Samantha and Lori Sally grew up outside Springdale, Arkansas a small industrial city where Tyson Foods, the massive chicken company, has its headquarters. Lori Elhassani

Samantha and Lori Sally grew up outside Springdale, Arkansas a small industrial city where Tyson Foods, the massive chicken company, has its headquarters.

Their father, Richard, was a long-haul trucker and Lisa, their mother, worked as an office manager at an air-conditioning company. They were strict Jehovah’s Witnesses who didn’t allow music or television in the home. Richard could be a fierce disciplinarian. Once when the sisters were caught jumping on the bed with their cousins, Lori says he beat them with a belt.

Richard and Sam both say Richard that was strict with the girls and corporal punishment was part of their childhood, but “my kids had a very good childhood,” Richard told me. “They were not abused.”

Lori was quiet and serious, while Sam was more of a free-spirited tomboy, always helping Richard fix up the car or run errands. The Sallys were strict about who the girls could be friends with, and didn’t allow them to go to friends’ houses. Whereas Lori was content to stay home alone with a book, Sam yearned for a life outside the confines of their strict religious upbringing, and delighted in rebelling against their parents in a way Lori found foreign. From the beginning the Sally sisters seemed built to function as a complementary pair: one sister’s strength was the other sister’s weakness.

Sam and Lori came from a family of strict Jehovah’s Witnesses who didn’t allow music or television in the home. Lori Elhassani

“Me and Lori were very close,” Sam told me. “We did everything together. Even when I grew up and I had girlfriends, my sister was always included. We were like best friends.”

When Sam and Lori were both young girls, Lori says they were repeatedly sexually assaulted by an adult relative. (Sam doesn’t deny there was sexual abuse, but says she doesn’t personally remember it happening.) Lori says she’d watched her community ostracize those who came forward with allegations of abuse, and believed she’d be punished if she tried to talk to her parents about it. Instead, she buried the trauma.

These two girls, their lives small and dented, tried to figure out how to be normal. As she grew into a young woman, Sam seemed to search for power, or at least the feeling of it. Starting around age 16 she found it in the men who blew in and out of her life like tornadoes in the Arkansas spring.

To Lori, who knew Sam better than anyone, Sam appeared intoxicated by the control she could exert over the boys, as if Sam was reminding herself that in spite of it all, she was invincible. This was all on the surface. Underneath: pain, and a deep-seated need for acceptance. “Everything with Sam is very glamour,” Lori says. “It’s very on the outside. It’s what she shows to you. But Sam herself? When I see her, I see a person who is broken into many, many pieces.”

One night while Lori was in bed, she heard Sam getting ready to go out partying. This had happened before, but this time Lori knew, somehow, in that way only sisters know, that Sam was leaving for good. Then the doorbell rang, and an older man Sam had met online walked into the foyer. Lori lost it. Usually, Sam was the one whose anger exploded into punches and screaming; Lori internalized her anger. But this time was different: Lori envisioned a life alone in that cold Arkansas farmhouse, and she snapped. She begged, she cried. She smacked Sam across the face. “I’m still leaving,” Sam said.

The sisters grew up best friends in Oklahoma. “Me and Lori were very close,” Sam said. “We did everything together.” Lori Elhassani

Sam’s marriage to Andrew Humphrey didn’t last long. The relationship was unhappy and full of abuse, including several instances in which Sam says he tried to kill her. Sam testified in a separate court hearing that she had been hospitalized for injuries allegedly inflicted upon her by Humphrey. “I think about it now, he was a predator, ” Sam told me later. “He was not the love of my life. He was more of an escape, I guess.”

Nor were Sam and Lori apart for long. Their young adult search for love took them to far away states and repeatedly brought them back to each other’s orbit. When the men and the cities let them down, they found each other.

Next for Sam was Juan Servantes, a former U.S. Navy soldier she met in 2004, when she was 19. The two had a child together—Matthew—and moved to Oklahoma. Juan took a job at a soda factory and they settled into a routine. It was the first time Sam’s life felt steady, like she wasn’t dangling off the edge of a cliff. But soon, Lori says, Sam was depressed about how formulaic her quiet life had become. Sam wanted more.

Samantha and Matthew before moving to Indiana and meeting Moussa. Samantha Elhassani

“Juan was a good man, he took care of me, he took good care of Matthew while we were there with him,” Sam told me “I was just … I don’t know…I guess ‘restless’ is the word.”

Lori, who had had a baby girl at age 17 and given custody to her parents, was married for a short time to Juan’s brother Tony, whom she met through Sam. She remembers staying with Sam and Juan in Oklahoma and noticing how despondent she’d become. Sam left Juan soon after that, eventually taking up with Raphael LeBraun, a long-haul trucker like her father.

Years later, after Sam had married a man from Morocco and moved to Syria and watched her husband join ISIS and escaped and ended up in jail, her friends from her previous life talked to CNN. They described a charismatic, outgoing woman who was always the life of the party. On Facebook, Sam posted selfies and sardonic memes, and showed a fondness for everything from souped-up cars to Vladimir Putin, whom she called “such a gangsta.” Sam was impossible to read. “She portrayed herself as a college graduate, business-minded, successful,” LeBraun said of their first meeting. “Later on I find out she never finished high school, was a troubled teen, heavily into drugs—not anyone that I would look for. I felt like I was fooled, bamboozled.” LeBraun was sure that Sam loved her son but he says, “Deep down inside I could see there was something wrong with her.”

Samantha, her grandmother, her mother Lisa and Lori. Lori is now estranged from the family. Lori Elhassani

Lori recalled Sam was so desperate for love and acceptance that even as a young girl she developed the ability to moderate her personality based on who was around. (“I’ve always prized myself on being able to read people and make friends and be very social,” Sam told me.) When she was home with her parents, Sam was a devout Jehovah’s Witness who dressed modestly and recited bible passages from memory, but when she was out with her friends, she became a hard-partying wild child.

“Sam is a chameleon,” Lori said. “She can become whatever she needs to be.”

Lori says the identity that Sam felt most comfortable was her own. Despite having a child at age 17, she eventually graduated from college, got a steady job and remained intellectually driven. Later, when Sam’s struggles in Syria brought Lori and LeBraun closer, he realized: That whole time they were together and Sam was trying to be someone she wasn’t? That was Sam, pretending to be Lori.

Sam, for her part, disputes these characterizations. “I was always the one who had a stable lifestyle and a good job,” she told me. “It wasn’t until I moved to Indiana that I relied on [Lori] for anything. I never looked at her for advice on anything. I never needed anything from her. I never got anything from her.”

The article was first published elle.com